Duchy of Warsaw

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2023) |

Duchy of Warsaw | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1807–1815 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lesser coat of arms: | |||||||||||||||||||||||

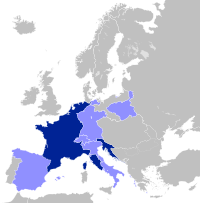

The Duchy of Warsaw in 1812 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Satellite state of the French Empire, Personal union with the Kingdom of Saxony | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Warsaw | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1807–1815 | Frederick Augustus I | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor-general of the Duchy of Warsaw | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1807-1809 | Louis-Nicolas Davout | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1807 | Stanisław Małachowski | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1807–1808 | Ludwik S. Gutakowski | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1808–1809 | Józef Poniatowski | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1809–1815 | Stanisław K. Potocki | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Sejm | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 June 1807 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 July 1807 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 April 1809 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 October 1809 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 June 1812 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 June 1815 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Złoty | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Poland Lithuania Belarus¹ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

¹ Sopoćkinie area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

The Duchy of Warsaw (Polish: Księstwo Warszawskie; French: Duché de Varsovie; German: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw[1] and Napoleonic Poland,[2] was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars. It initially comprised the ethnically Polish lands ceded to France by Prussia under the terms of the Treaties of Tilsit, and was augmented in 1809 with territory ceded by Austria in the Treaty of Schönbrunn. It was the first attempt to re-establish Poland as a sovereign state after the 18th-century partitions and covered the central and southeastern parts of present-day Poland.

The duchy was held in personal union by Napoleon's ally, Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, who became the duke of Warsaw and remained a legitimate candidate for the Polish throne. Following Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia, Napoleon seemingly abandoned the duchy, and it was left to be occupied by Prussian and Russian troops until 1815, when it was formally divided between the two countries at the Congress of Vienna. The east-central territory of the duchy acquired by the Russian Empire was subsequently transformed into a polity called Congress Poland, and Prussia formed the Grand Duchy of Posen in the west. The city of Kraków, Poland's cultural centre, was granted "free city" status until its incorporation into Austria in 1846.

History

[edit]The area of the duchy had already been liberated by a popular uprising that had escalated from anti-conscription rioting in 1806. One of the first tasks for the new government included providing food to the French army fighting the Russians in East Prussia.

The Duchy of Warsaw was created by French Emperor Napoleon I, as part of the Treaty of Tilsit with Prussia. Its creation met the support of both local republicans in partitioned Poland, and the large Polish diaspora in France, who openly supported Napoleon as the only man capable of restoring Polish sovereignty after the Partitions of Poland of the late 18th century. However, it was created as a satellite state[3] (and was only a duchy, rather than a kingdom). The Duchy has also been described as a puppet state[4][5][6] or a client state[7][8] of Napoleon's France.

The newly recreated state was formally an independent duchy, allied to France, and in a personal union with the Kingdom of Saxony. King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony was compelled by Napoleon to make his new realm a constitutional monarchy, with a parliament (the Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw).

The Varsovian duchy was never allowed to develop as a truly independent state; Frederick Augustus' rule was subordinated to the requirements of the French raison d'état, who largely treated the state as a source of resources. The most important person in the duchy was, in fact, the French ambassador,[citation needed] based in the duchy's capital, Warsaw. Significantly, the duchy lacked its own diplomatic representation abroad.[9]

In 1809, a short war with Austria started. Although the Duchy of Warsaw won the Battle of Raszyn, Austrian troops entered Warsaw, but Varsovian and French forces then outflanked their enemy and captured Kraków, Lwów and some of the areas annexed by Austria in the Partitions of Poland. During the war, the German colonists settled by Prussia during Partitions openly rose up against the Varsovian government.[10] After the Battle of Wagram, the ensuing Treaty of Schönbrunn allowed for a significant expansion of the duchy's territory southwards with the regaining of once-Polish and Lithuanian lands.

Peninsular War

[edit]Napoleon's campaign against Russia

[edit]

As a result of Napoleon's campaign in 1812 against Russia, the Poles expected that the duchy would be upgraded to the status of a kingdom and that during Napoleon's invasion of Russia, they would be joined by the liberated territories of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Poland's historic partner in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. On 28 June, the Sejm formed the General Confederation of the Kingdom of Poland, establishing a system of government similar to the former commonwealth with the hope of reclaiming the partitioned territories. However, Napoleon did not want to make a permanent decision that would tie his hands before his anticipated peace settlement with Russia, and did not recognize the confederation of 28 June. Nevertheless, he proclaimed the attack on Russia as a second Polish war and allowed the Lithuanian Provisional Governing Commission to fall under Polish influence.

Any peace settlement or restoration of Poland-Lithuania were not to be, however. Napoleon's Grande Armée, including a substantial contingent of Polish troops, set out with the purpose of bringing the Russian Empire to its knees, but his military ambitions were frustrated by his failure to supply the army in Russia and Russia's refusal to surrender after the capture of Moscow; few returned from the march back. The failed campaign against Russia proved to be a major turning point in Napoleon's fortunes.

After Napoleon's defeat in the east, most of the territory of the Duchy of Warsaw was occupied by Russia in January 1813 during their advance on France and its allies. The rest of the duchy was restored to Prussia. Although several isolated fortresses held out for more than a year, the existence of the Varsovian state in anything but the name came to an end. Alexander I of Russia created a Provisional Highest Council of the Duchy of Warsaw to govern the area through his generals.

The Congress of Vienna and the Fourth Partition

[edit]Although many European states and ex-rulers were represented at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the decision-making was largely in the hands of the major powers. It was perhaps inevitable, therefore, that both Prussia and Russia would effectively partition Poland between them; Austria was to more-or-less retain its gains of the First Partition of 1772.

Russia sought all territories of the Duchy of Warsaw. It kept all its gains from the three previous partitions, together with Białystok and the surrounding territory that it had obtained in 1807. Its demands for the whole Duchy of Warsaw were denied by other European powers.

Prussia regained some of the territory it had lost to the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807: a portion of what it had conquered in the Second Partition. The Kulmerland and Gdańsk (Danzig) became part of the Province of West Prussia; the remaining territories (i.e., Greater Poland/Poznań), which covered an area of approximately 29,000 km2 (11,000 sq mi), were reconstituted into the Grand Duchy of Posen. The Grand Duchy and its populace had some nominal autonomy (although it was de facto subordinate to Prussia) but following the 1848 Greater Poland Uprising was fully integrated into Prussia as the Province of Posen.

The city of Kraków and some surrounding territory, previously part of the Duchy of Warsaw, were established as the semi-independent Free City of Cracow [sic], under the "protection" of its three powerful neighbors. The city's territory measured some 1,164 km2 (449 sq mi), and had a population of about 88,000 people. The city was eventually annexed by Austria in 1846, becoming the Grand Duchy of Kraków.

Finally, the bulk of the former Duchy of Warsaw, measuring some 128,000 km2 (49,000 sq mi), was re-established as what is commonly referred to as the "Congress Kingdom" of Poland, in a personal union with the Russian Empire. This broadly corresponded to the Prussian and Austrian portions of the Third Partition (apart from the area around Białystok) plus around half of Prussia's Second Partition conquests and a small part of Austria's First Partition gains. De facto a Russian puppet state, it maintained its separate status only until 1831 when it was effectively annexed to the Russian Empire. Its constituent territories became the Vistula Land in 1867.

Government and politics

[edit]Constitution

[edit]

The Constitution of the Duchy of Warsaw could be considered liberal for its time. It provided for a bicameral Sejm consisting of a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies. A Council of Ministers functioned as the executive body of the duchy. Serfdom was partially abolished, as the serfs were granted personal freedom without gaining any economic liberties or privileges. All classes were to be equal before the law, although the nobility was still greatly favoured as members of the Sejm. While Roman Catholicism was the state religion, and religious tolerance was also guaranteed by the constitution.

Administrative divisions

[edit]The administrative divisions of Duchy of Warsaw were based on departments, each headed by a prefect. This organization was based on the French model, as the entire duchy was in fact created by Napoleon and based on French ideas, although departments were divided into Polish powiats (counties).

There were 6 initial departments, after 1809 (after Napoleon's defeat of the Austrians and the Treaty of Schönbrunn) increased to 10 (as the duchy territory increased). Each department was named after its capital city.

In January 1807:

- Warsaw Department (Polish: Departament warszawski)

- Poznań Department (Polish: Departament poznański)

- Kalisz Department (Polish: Departament kaliski)

- Bydgoszcz Department (Polish: Departament bydgoski)

- Płock Department (Polish: Departament płocki)

- Łomża Department (Polish: Departament łomżyński) – for the first few months known as Białystok Department (Polish: Departament białostocki)[citation needed]

The above 6 departments were divided into 60 powiats.

Added in 1809:

- Kraków Department (Polish: Departament krakowski)

- Lublin Department (Polish: Departament lubelski)

- Radom Department (Polish: Departament radomski)

- Siedlce Department (Polish: Departament siedlecki)

Military

[edit]The duchy's armed forces were completely under French control via its war minister, Prince Józef Poniatowski, who was also a Marshal of France. In fact, the duchy was heavily militarized, bordered as it was by Prussia, the Austrian Empire, and Russia, and it was to be a significant source for troops in various campaigns of Napoleon.

The duchy's army was of considerable size when compared to the duchy's number of inhabitants. Initially consisting of 30,000 of regular soldiers (made up of both cavalry and infantry),[11] its numbers were to rise to over 60,000 in 1810, and by the time of Napoleon's campaign in Russia in 1812, its army totaled almost 120,000 troops out of a total population of just 4.3 million people – a similar number of troops in total available to Napoleon at Austerlitz, from a country of more than 25 million people.

Economy

[edit]The heavy drain on its resources by forced military recruitment, combined with a drop in exports of grain, caused significant problems for the duchy's economy. To make matters worse, in 1808 the French Empire imposed on the duchy an agreement at Bayonne to buy from France the debts owed to it by Prussia.[12] The debt, amounting to more than 43 million francs in gold, was bought at a discounted rate of 21 million francs.[12]

Although the duchy made its payments in installments to France over a four-year period, Prussia was unable to pay it (due to a very large indemnity it owed to France), causing the Polish economy to suffer heavily. Indeed, to this day the phrase "sum of Bayonne" is a synonym in Polish for a huge amount of money.[12] All these problems resulted in both inflation and over-taxation.

To counter the threat of bankruptcy, the authorities intensified the development and modernization of agriculture. Also, a protectionist policy was introduced to protect industry.

Geography and demographics

[edit]According to the Treaties of Tilsit, the area of the duchy covered roughly the areas of the 2nd and 3rd Prussian partitions, with the exception of Danzig (Gdańsk), which became the Free City of Danzig under joint French and Saxon "protection", and of the district around Białystok, which became part of Russia. The Prussian territory was made up of territory from the former Prussian provinces of New East Prussia, Southern Prussia, New Silesia, and West Prussia. In addition, the new state was given the area along the Noteć river and the Land of Chełmno.

Altogether, the duchy had an initial area of around 104,000 square kilometres (40,000 sq mi), with a population of approximately 2,600,000. The bulk of its inhabitants were Poles.[13]

In 1809 the Duchy annexed West Galicia, the area of the 1795 Austrian partition, and the district of Zamość (Zamoscer Kreis): The duchy's area increased significantly, to around 155,000 km2 (60,000 sq mi), and the population also substantially increased, to roughly 4,300,000.

According to the 1810 census, the duchy had a population of 4,334,000, of whom a clear majority were ethnic Poles. Jews constituted 7% of the inhabitants (perhaps an underestimation), Germans – 6%, Lithuanians and Ruthenians – 4%.[14]

Legacy

[edit]Superficially, the Duchy of Warsaw was just one of the various states set up during Napoleon's dominance over Eastern and Central Europe, lasting only a few years and passing with his fall. However, its establishment a little over a decade after the Second and Third Partitions, that had appeared to wipe Poland off the map, meant that Poles had their hopes rekindled of a resurrected Polish state. Even with Napoleon's defeat, a Polish state continued in some form until the increasingly autocratic Russian state eliminated Poland once again as a separate entity. Altogether, this meant that an identifiable Polish state was in existence for at least a quarter of a century.

At the 200th anniversary of the creation of this iteration of the Polish state, numerous commemorative events dedicated to that event were held in the Polish capital of Warsaw. In addition, the Polish Ministry of Defense asked for the honor of holding a joint parade of Polish and French soldiers to which President Nicolas Sarkozy agreed.[15]

See also

[edit]- History of Poland (1795–1918)

- Polish Legions (Napoleonic period)

- Legion of the Vistula

- 1st Polish Light Cavalry Regiment of the Imperial Guard

- Army of the Duchy of Warsaw

- Greater Poland uprising (1806)

- Congress Poland

- List of French possessions and colonies

References

[edit]- ^ "A Guide to the United States' History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Poland". US Department of state. Archived from the original on 2020-07-21. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Poland. Cambridge University Press. 15 September 2016. ISBN 9781316620038.

- ^ Williamson, David G. (2011). Poland Betrayed: The Nazi-Soviet Invasions of 1939. Stackpole Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8117-0828-9.

- ^ Bilenky, Serhiy (2022). "Vadym Adadurov. "Napoleonida" na skhodi Ievropy: Uiavlennia, proekty ta diial'nist' uriadu Frantsii shchodo pivdenno-zakhidnykh okrain Rosiis'koi imperii na pochatku XIX stolittia". East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 9 (1): 253–258. doi:10.21226/ewjus717. ISSN 2292-7956. S2CID 247911190.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita (30 June 2010). Poland: A Modern History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85773-677-2. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

As a result of this, the Duchy of Warsaw was created.... Nevertheless, although a French puppet state, the Duchy was...

- ^ Summerville, Christopher (30 September 2005). Napoleon's Polish Gamble: Eylau & Friedland 1807 – Campaign Chronicles. Pen and Sword. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-84415-260-5.

- ^ Wroński, Marcin (2 December 2022). "Income inequality in the Duchy of Warsaw (1810/11)". Scandinavian Economic History Review. 72: 67–81. doi:10.1080/03585522.2022.2148736. ISSN 0358-5522.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (1994), Lyons, Martyn (ed.), "The Unsheathed Sword, 2: Britain, Spain, Russia", Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 213–228, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-23436-3_15, ISBN 978-1-349-23436-3, retrieved 10 May 2023

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (2014). Napoleon: A Life. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780698176287. chap. 19 (no pg. no. in e-book).

- ^ Kolonizacja niemiecka w południowo-wschodniej cześci Królestwa Polskiego w latach 1815–1915 Wiesław Śladkowski Wydawn. Lubelskie, 1969, page 234

- ^ Wandycz, Piotr S. (1 February 1975). The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795–1918. University of Washington Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-295-80361-6.

- ^ a b c Paul Robert Magocsi; Jean W. Sedlar; Robert A. Kann; Charles Jelavich; Joseph Rothschild (1974). A History of East Central Europe. University of Washington Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-295-95358-8. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ "ВАРШАВСЬКЕ КНЯЗІВСТВО [Електронний ресурс]". ІНСТИТУТ ІСТОРІЇ УКРАЇНИ. НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ НАУК УКРАЇНИ.

- ^ Czubaty, Jarosław (2016). The Duchy of Warsaw, 1807–1815: A Napoleonic Outpost in Central Europe. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 109.

- ^ "Rp.pl: Najważniejsze wiadomości gospodarcze, prawne i polityczne z Polski i ze świata. Aktualne wiadomości z dnia – rp.pl". www.rp.pl. Archived from the original on 2020-08-26. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Martyna Deszczyńska. "'As Poor as Church Mice': Bishops, Finances, Posts, and Civil Duties in the Duchy of Warsaw, 1807–13," Central Europe (2011) 9#1 pp 18–31.

- E. Fedosova (December 1998), Polish Projects of Napoleon Bonaparte, Journal of the International Napoleonic Society 1(2)

- Alexander Grab, Napoleon and the Transformation of Europe (2003) pp 176–87

- Otto Pivka (2012). Napoleon's Polish Troops. Osprey Publishing. pp. 8–10. ISBN 9781780965499.[permanent dead link]